The Making of Lemmings

How DMA Design created a classic, and what happened next

If a young electronics engineer named David Jones hadn’t lost his job at the Timex plant in Dundee in 1988, videogame history would have been different. Already a keen programmer, Jones used his £3000 redundancy cheque to invest in a top-of-the-range Amiga 1000 and begin taking software engineering classes, to the chagrin of his parents, who saw a better future in his hardware expertise.

Jones hung out at the Kingsway Amateur Computer Club in Dundee with other young programmers like Mike Dailly, Steve Hammond, and Russell Kay. They all made games, sometimes together, several of which saw release.1 With his Amiga 1000 the envy of all, Jones began working on a Salamander-inspired shooter nicknamed ‘CopperCon1’. With a little help from his friends the game looked so promising it was signed by publisher Psygnosis, a huge cheese in the 1980s videogame industry. Jones soon set up Direct Memory Access Design (‘DMA’) and, basically, began employing his mates.

This small studio would go on to create the Grand Theft Auto series, among many other great games, and would have an enormous influence on the industry. ‘CopperCon1’ was released as Menace in 1988 and became a minor hit. It was followed by an even better shooter called Blood Money. These first games were far from original in their sci-fi settings and power-ups, which were heavily inspired by the side-scrolling coin-op arcade games DMA’s coders enjoyed playing themselves, but they were distinguished by great visuals, and a smart sense of what to nick from elsewhere and what to leave out.

DMA’s first wholly original project began to take shape soon after Blood Money’s completion, and it would be a game so unusual that nothing before or since compares. The origins of Lemmings were in a sprite created for Blood Money; an ED-209-esque enemy called ‘the Walker’. The Walker looked so good and had such great animations that David Jones believed DMA could build a game around it. The team started to come up with ideas, one of which centred on the troops that fought against the giant bipedal mech, and specifically how their little 16×16 sprites had helped to emphasise its formidable stature.

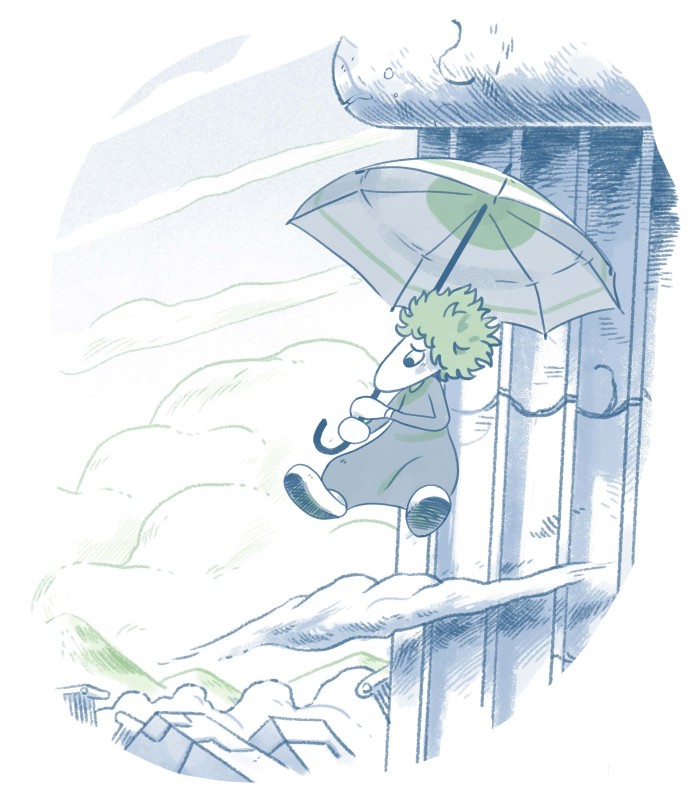

Mike Dailly had seen tiny 5-pixel high sprites in games like Oids2 , a popular Atari ST shooter where the player’s ship rescued little android slaves, and thought that somewhere between this and a 16×16 sprite would be a sweet spot – where the small size made the Walker look big by comparison, but the animations were still good enough to impart character. One lunchtime he made an image of little men being crushed by weights, and shot by a laser gun – everyone loved it, and Gary Timmons added a few more traps. While everyone was laughing, Russell Kay was the first to say ‘There’s a game in that!’

Kay had also recently figured out how to make objects track terrain while working on Blood Money, intending to make a Salamander-style bullet that moved across a level’s surface (though it never made the final game). To Kay, the tiny men and the terrain-tracking code seemed a perfect match, and he put together a demo for Psygnosis in late 1989. At the time, David Jones had also been working on something of a passion project that allowed him to combine his electrical engineering and software skills: the Monster Cartridge, an Action Replay device for the Amiga. But although publisher Datel was interested, Jones kept hitting fiddly problems with the device, and DMA was eventually beaten to the punch by another company. The Monster Cartridge’s failure meant that Lemmings became the studio’s main focus.

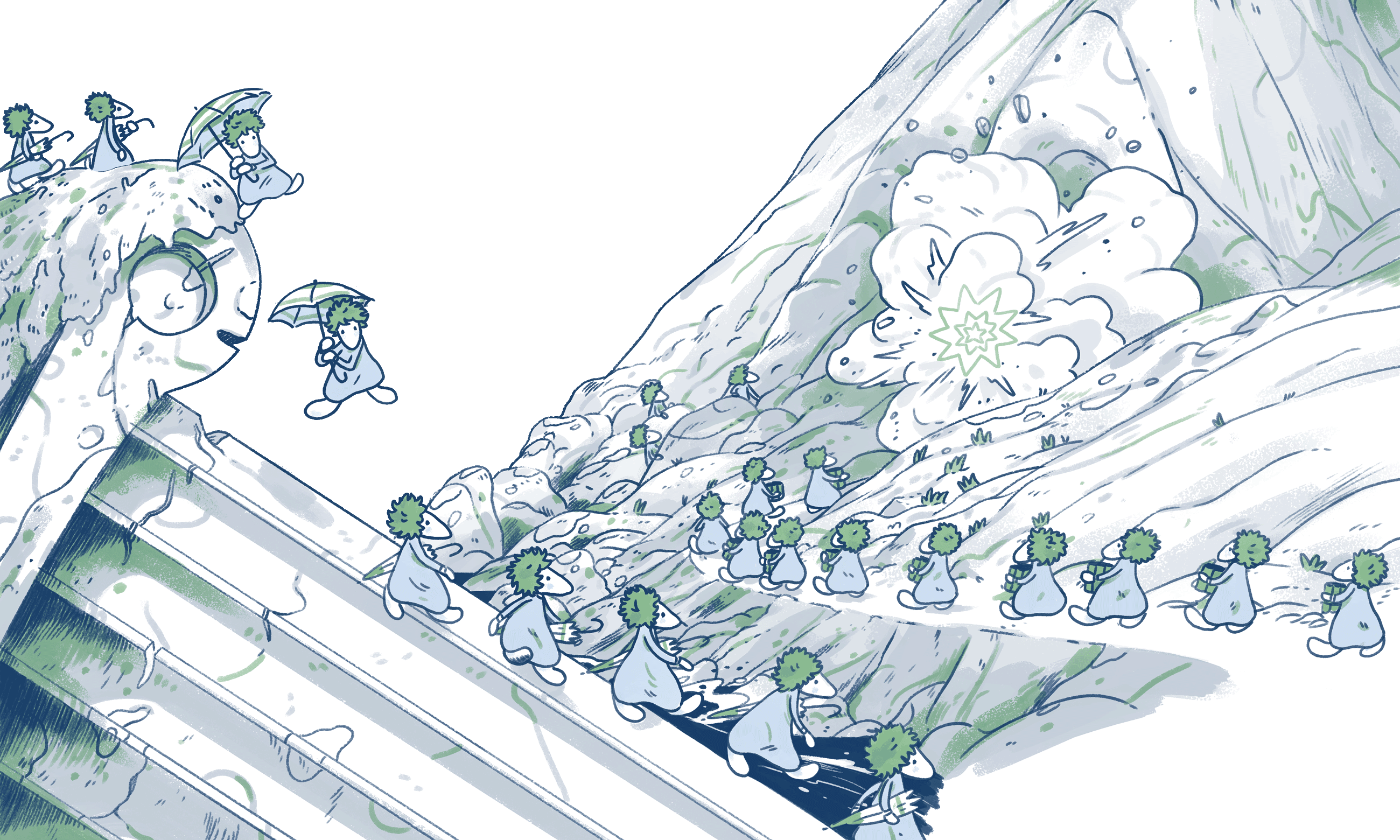

‘The goal was to get the sprites to 8×8,’ explains Dailly, ‘but they actually ended up about 8×10 – hardly anyone has ever noticed this figure was wrong.’ The flipside of going for such small characters was that you could have a lot of them: DMA decided to aim for a hundred lemmings on-screen. ‘It was a nice, round, high number,’ says Dailly. ‘Normally we’d have gone for 64 or 128, but 128 would have been pushing it. And it also lent itself to 100%, so on busy levels you had to save all of them.’

Very early in development the team knew killing lemmings was entertaining, with traps already including hands that squashed the unfortunate creatures together and fans that chopped them up. As work progressed, they implemented even more dastardly devices: mincers, flamethrowers, horrible nooses. ‘We liked to kill lemmings in funny ways, and this was the comedic nature of the game coming through,’ says Dailly. ‘Lemmings were expendable. [The traps] really were there to just help guide the player around, otherwise many levels would have been dreadfully dull.’

But it was never a game about killing lemmings. ‘You always had to save them,’ says Dailly, ‘And the nuke was always a way to abort the level. It’s one of the few original games I’ve worked on where the core idea never changed much.’ This hints at one of the quieter revolutions involved in the development of Lemmings. At the time, a developer would typically code their game, then export it to an editor to check it worked. But for Lemmings DMA created an integrated tool for designing the levels, based on the interface of the Amiga’s Deluxe Paint program, which allowed anything built or changed to be tested immediately. This made the construction of Lemmings’ levels a much faster, more iterative process.

At the core of the game is a brilliant original idea. You apply one of eight abilities to the lemmings, which all have obvious uses but can also follow on and interrupt each other to offer new possibilities. These can be simple and natural – transitioning a digger into a floater – or fiendish tests of multitasking and timing. Try catching a digger as a floater, turning him into a blocker, catching the lemmings behind him as floaters, then grabbing one to build a bridge up as a landing pad before you run out of brollies. Later levels ask for enormous precision, making you land lemmings on tiny pillars, bounce bridges around the landscape, and carve mercilessly through the terrain.

The blocker has one of Lemmings’ most delightful kinks, in that it stands in one spot blocking other lemmings and can’t be returned to a walking motion – but you can dig it out. Though not always possible, ‘saving’ blockers rather than blowing them up becomes a minor badge of pride and, later in the game, an essential skill. ‘Yeah on some of the later, harder levels you had to save them,’ laughs Dailly. ‘It was tricky, but possible. You’d basically use a digger, miner, or basher to dig the ground away from under their feet, and then quickly build, which would stop the digger or miner and save that character as well. The blocker would then fall, and return to his default state, if there was no ground under their feet to support him.’ Did DMA consider a ‘return to walking’ command to make saving blockers easier? ‘Returning to walking was a cop-out,’ says Dailly. ‘And the digging under the feet was much harder and a great challenge for later levels.’ This refusal to cop-out and fudge the hard edges of the design is what makes Lemmings so enduring: the precision, the smooth learning curve, the short levels, the tactile terrain, and the simple slapstick that made getting it wrong enjoyable anyway.

At its core, however, is something sweet. The characters and objective tap into a minor strain of folklore: the idea that real lemmings follow each other to death en masse. As with many myths, there’s a truth somewhere. Lemmings often die in large numbers because they migrate in large numbers, and choose a bad spot to cross a river. Their populations fluctuate from year to year. In the popular imagination, for some reason, we interpret this as consistent and collective suicide. Which is why the twist of Lemmings – that you can save these leaderless creatures – intrigues our inner logic and strokes the ego. But it’s also unusual for a game to focus on saving things. We’re used to, even numb to gunning down hordes of foes, flambéing wildlife, and destroying cities. That’s all great, and DMA’s initial games were shooters, inspired by what the young designers had loved growing up.

Lemmings simply offers something different. The sprites with flouncy hair soon become friends, their dedication and helplessness an irresistible pull. The size of the lemmings, that first impulse behind their creation, has the neat effect of making minor hills huge and half-screen gaps cavernous, thus ennobling their acts. The animations shine with personality: the sheer exertion in every swing of a basher’s hands, captured in that split-second the limb is held aloft before crashing down. And Gary Timmins, the animator and one of the level designers on Lemmings, points out that the builder ‘shrugging’ when it has finished building wasn’t just a neat piece of characterisation – it also gives the player more time to react. The sprites cease to be an 8×10 grid of pixels, and become lemmings, looking to the player for direction and salvation. This mix of buttons that Lemmings pushes in a player – caring and bloodthirsty – still feels fresh. As the release date loomed, DMA and Psygnosis realised that this might be a problem. Lemmings was, in Jones’ words, an ‘impossible game to describe’ and therefore a marketing nightmare. But it wasn’t complex – people just had to play it to understand the appeal. The strategy was to get as many demos out as possible, which in 1990/1991 meant a tonne of magazine covermounts.

Interestingly, the heroic quality of Lemmings may have been even more pronounced if the working music had made the final version. DMA had made a decision, mostly in innocence, to rip off famous action themes for the levels’ music. ‘We only had a couple of tunes,’ says Dailly. ‘Mission Impossible was the one we all remember … but I know we had a few. It was supposed to be ‘60s/‘70s action music.’ There was also a version of The A-Team theme. At the last minute DMA and Psygnosis realised Lemmings would be wide open for a copyright suit, and decided to go for a quick re-do based around the music of dead people who couldn’t sue. Composer Tim Wright pulled Lemmings out of the fire with style, bouncily reinterpreting standards like Offenbach’s Galop Infernal and Ten Green Bottles, and adding a touch of class with Tchaikovsky’s Dance of the Little Swans.

Jones estimates that Lemmings cost around £100,000 to make, and took around a year in total to develop: longer than was usual at the time. In the Abertay University talk, he also recalls it was partly funded by royalties (75p per £25 sale) from DMA’s first two games. Menace and Blood Money had racked up lifetime sales of 20,000 and 40,000 copies respectively.

When Lemmings was released in February 1991 for the Amiga, it sold 55,000 copies on the first day. While DMA busied itself with porting the game to as many platforms as possible, it kept selling. Soon word-of-mouth took Lemmings global and over the next 15 years and many platforms it would sell an estimated 15 million copies. Such success was a dream for independent developers like DMA, but it was equally a surprise. ‘We knew it was good, because we all loved making levels and playing with it,’ says Dailly. ‘We never knew just how big it was going to be – and even after launch had no real idea, as Dave never told us the numbers until the mid 2000s! But once the reviews started hitting, and we were getting 10/10 and 100%, we guessed we were onto something big.’ The fact that the studio now had a top-selling game on around 30 platforms made post-launch support a constant drain on resources. Russell Kay, who made the first demo, spoke at Dundee’s Abertay University on the game’s 20th anniversary and paused after recalling this era to confess, ‘I used to dream of lemmings.’

Over the following years, DMA would make two main sequels as well as spinoffs like Oh No! More Lemmings, Christmas Lemmings, Windows Lemmings, and Lemmings Paintball. Lemmings 2: The Tribes was released in 1993 and added a tonne of abilities as well as theming the levels around a dozen tribes. ‘Lemmings 2 was a different beast,’ says Dailly. ‘The tech was much more complex, but designed to make console versions much better. I think it had too many skills, but the underlying tech was great. I was given the SNES version to do, and it was one of the most complex games I’ve had to write. Some complex internals that had to run quick on a 3.5Mhz chip. Tricky stuff – but fun!’

Lemmings 2 was, at least, a great game made by a studio that wasn’t sick of Lemmings. By the time of the third and last main entry, DMA’s farewell to the series, the studio wanted to move in other directions but was being pushed and pulled by the influence of success. ‘Lemmings 3 was a bit crap … more to end our commitment to Psygnosis than actually do a good game,’ admits Dailly. ‘The larger character size really spoiled it, but it was done like that because we had been approached by The Children’s Television Workshop who wanted to use the character and the game; they wanted the characters to be bigger, and that really complicated things, and spoilt it. By the end of Lemmings 3, I think we were all ready to move on.’

Lemmings was made on Amiga 500s with no hard drives or internet connection, with all the files saved on floppies. This is one of the reasons that the making of Lemmings has gaps of material and versions lost to time. But if you ever visit Perth Road in the centre of Dundee, you can see DMA Design’s old office at the far west end. A few hundred yards away is a park called Seabraes and here, in front of the entrance to Dundee’s digital media park, you can find a pillar with three bronze lemmings clambering up and over it. It’s a nice piece of public art, a reminder of Dundee’s creative reach and an aspirational marker for its young would-be developers. But for the characters it’s also something of a monument. DMA moved away from Lemmings after the third main entry, and the series has never fared well since. In 2014 it’s not even possible to buy a modern PC version. You get this sense, however unquantifiable, that Lemmings was never quite as influential as it should have been.

Thanks to its purchase of Psygnosis, Sony holds the rights to Lemmings. It doesn’t seem to be doing anything with them. It is the way of the world that DMA’s most vibrant legacy is the game they made about crime and shooting rather than the one about saving little creatures. ‘I would have loved to take the characters and do something different with them,’ says Dailly. ‘But we never got the chance. When you get down to it the original game was brilliant, and the sequel had brilliant tech. But the characters themselves are what makes the game. And they should be used for more, for far more.’

In today’s nostalgia-hungry industry the return of Lemmings is hopefully a matter of time. Updating a classic is never easy, of course, but the game is so original and well-loved it’s amazing no-one has tried to do what Championship Edition did for Pac-Man. That may be Lemmings’ beauty and its curse. There is not a single element of the game that could be removed without changing the whole thing. Adding more stuff, as with the sequel, doesn’t make it better. And how can you update visuals that are iconic because they’re 8×10 sprites?

Lemmings is still waiting for its remastered version, updated and improved for a new generation; but then Lemmings had a problem most other games don’t: it was already perfect the first time around.

Footnotes

- 1 Mike Dailly and Steve Hammond collaborated on Freek Out, a simple Breakout-type game with Dailly coding and Hammond handling the visuals. Russell Kay’s Zone Trooper was published by Gamebusters for the Spectrum, Amstrad and Commodore 64. A Jetpac-style platformer, it was of course a sophomore effort and as such received a monstering in the day's press.

- 2 A fast-paced arcade-style shooter, Oids was released in 1987 for the Atari ST and Apple Mac. It was developed by the California-based FTL Games, a three-person team composed of Nancy Holder, Wayne Holder and Bruce Webster. Though the studio was only active for just over a decade, it developed several fine titles including Sundog and Dungeon Master. Oids’ title, interestingly enough, is most probably an abbreviation of the computing term ‘object identifier.’