John Madden Hockey

How a lousy football game birthed a bastard and led to the greatest hockey game of all-time

Ken Baumgartner was angry.

And much like the Incredible Hulk, Ken Baumgartner – 6’1”, 205 pounds, with a penchant for doling out punishment – was not the kind of guy you wanted to see angry. Baumgartner was a left wing for the Toronto Maple Leafs. More specifically, he was their enforcer; a man paid literally to inflict pain on opponents. But in 1992, the target of his aggression was not another player; nor was it a coach or referee. It was a videogame producer at Electronic Arts named Michael Brook.

Outside an NHL Players Association (NHLPA) meeting held in San Diego, where players had gathered to discuss licensing opportunities, Baumgartner lumbered towards the young producer.

‘Hi, I’m Ken Baumgartner,’ he said flatly by way of introduction. As a lifelong hockey fan, Brook already knew who he was, and indicated as much with a tiny flinch of a smile. Despite the recognition, the thuggish enforcer felt compelled to further introduce himself:

‘I’m the guy you gave a zero rating to for Intelligence.’

Oh my god, Brook thought, growing red in the face.

What he didn’t realise at the time was that the beta version of his new hockey game, NHLPA Hockey ’93, had been the highlight of the licensing meeting. But the players had been interested not so much in the game itself, as in the ratings that Electronic Arts had awarded them for categories like Passing, Agility, and of course, Intelligence. That’s when Baumgartner had noticed that his 16-bit self was a dunce. To make matters worse, this detail hadn’t escaped the attention of the other players around the conference table, who seemed unable to stop laughing.

Intellectually, Michael Brook had always known that his sports games were based on real people, but this was the first time that the notion really hit him on an emotional level: EA’s hockey games had become so popular that the hockey players themselves actually took notice.

Confronted by Baumgartner, a part of Brook wanted to wilt in embarrassment. Another part of him felt like pointing out that for a guy who had played 55 games, scoring zero goals while racking up 225 penalty minutes, maybe that zero was appropriate. But the part of Brook that wished to avoid becoming Baumgartner’s punching bag won out. He tactfully explained that there must have been some mistake, and promised to give this issue his full attention.

True to his word, he was able to change the name of the category from Intelligence to Offensive Awareness. But it was too late to change the zero. So Brook mentally added this to his running list of things to change for EA’s next annual hockey game, which would go on to become one of the most beloved sports games of all-time: NHL ’94.

Art vs. Commerce

In order to understand why the stars would align for NHL ’94, it’s important to explore the constellation of ideas, events and personalities that led to its creation. The best place to begin is with Trip Hawkins, who founded Electronic Arts in 1983 with the noble vision of turning computer programmers into rock stars.

Hawkins’ plan was to empower the artists responsible for the latest and greatest computer games by turning them into the Billy Joels and Bruce Springsteens of the gaming industry. But although EA’s early titles like Pinball Construction Set and M.U.L.E. received critical acclaim, the creators of those games – Bill Budge and Danielle Bunten Berry, respectively – had little opportunity to become household names, partly because in 1983 most households did not contain personal computers; and those that did tended to be used for business more than pleasure.

The landscape started to change in 1985, when Nintendo launched their 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the United States. The NES wasn’t quite a PC, but it did bear it a cousinly resemblance. As a dedicated videogame console, it appeared to be a match made in heaven for Electronic Arts, but Hawkins resisted the love connection for a variety of reasons.

For starters, he believed that the NES would be a flash in the pan. Fantastic today, forgotten tomorrow; destined for the same pitiful fate as all those previous consoles that had instantly become obsolete due to the videogame crash of 1983. Also, Nintendo’s unusually strict licensing agreement required publishers to develop games exclusively for the NES. Considering that in the PC world, EA had free reign to develop for a host of different platforms, including the Amiga, the Apple II and the Commodore 64, it’s easy to understand why Hawkins decided to stay away from Nintendo.

Despite Hawkins’ initial reservations, it soon became clear that the NES was destined for greater things than the previous console generation, and presented a lucrative opportunity for developers who were willing to sign that licensing agreement. But his resistance to the lure of the NES was also motivated by creative concerns. Electronic Arts had been founded as something of an artistic sanctuary: Hawkins constantly preached a philosophy of making games that were ‘simple, hot and deep’, and it was far from clear that a NES game could encapsulate these principles. Simple? Probably. Hot? Possibly. But deep? Not even close, when compared to the power of a personal computer.

To a degree, then, a battle developed between Art and Commerce, and with Trip Hawkins at the helm, Art would be the winner. To help give Art the upper hand, Hawkins brought in a bunch of business-minded executives with a passion for games. People like Michael Brook.

Everbrook

Some people believe they are destined for greatness. Michael Brook certainly hoped that this would be the case, but in the meantime he believed he was destined for games. As a boy, Brook loved sports so much that he’d taught himself statistics and probability; and by the time he was a teenager, he’d started a company called Everbrook Games, selling tabletop games that he personally designed through the mail.

During the second year of his MBA at Stanford Business School, a colleague of Trip Hawkins learned about Brook’s love for making games and set up an informal meeting between the pair. They immediately hit it off, and what was supposed to be only a thirty-minute meet and greet stretched into a two-hour conversation that ended with Hawkins asking Brook to become his assistant.

After spending his second year at Stanford moonlighting for Trip, Brook found it an easy decision to join EA full-time when he graduated. At 24 years old, Michael Brook felt like he was living happily ever after.

The snag, however, was timing. In 1987, EA were hurting for cash and planned to rectify this by going public. Unfortunately, with the stock market crash in October of that year, the company found itself in an unfortunate situation; too late for an IPO and too early for the PC revolution (which had been delayed, in part, by Nintendo’s home console revolution). Meanwhile, Brook was offered a lucrative opportunity to work in Amsterdam for two years and didn’t know what to do. Stay with a company he loved, but which might not exist in six months? Or take the money and run off to Europe? Ultimately it was Hawkins – mentor, boss and friend – who convinced Brook to follow his wanderlust, and give Europe a try.

‘But when you’re ready to come back,’ Hawkins said, as optimistic as ever about EA’s future, ‘just let me know.’

Simple. Hot. Deep.

John Madden vs. Don Badden

Although much of EA’s early reputation as a publisher had been built on critically acclaimed action/adventure titles, the company was beginning to garner attention for producing high quality sports games. They’d dribbled onto the scene with a basketball game called One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry (1983), teed off next with World Tour Golf (1985) and then knocked it out of the park with Earl Weaver Baseball (1987), which Computer Gaming World called ‘The most exciting sports simulation to be released in years.’ High praise, but EA was just getting started. When it came to equipping players with a digital jockstrap, the company’s crown jewel was supposed to be a football game.

Not just any football game, but the first realistic one! It would have eleven players on each side, detailed stats and plays designed by John Madden himself. EA had even obtained the exclusive rights to use the Super Bowl winning coach’s name and likeness. With pedigree like that, what football fan could possibly resist?

The answer? Nobody knew, because the game was taking so damn long to finish. Trip Hawkins had hired a programmer named Robin Antonick to code this groundbreaking football title back in 1983 and still it remained incomplete.

Much like EA itself, development of John Madden Football began with seemingly sound artistic and commercial ambitions, but four years later it was sputtering in place. Hawkins blamed Antonick for programming too slowly, Antonick blamed Hawkins for changing his mind too much, and EA’s employees couldn’t help but blame the company’s financial woes in part on this seemingly cursed game. With the 8-bit gold rush now in full swing, many employees were also wondering whether it might be time to end these woes by porting games to the NES.

Hawkins, however, remained staunchly anti-console. The constant development costs of this football game were painful, but not quite crippling. What hurt more was the realisation that something conceived as groundbreaking in 1983 was now, five years later, more commonplace. By the time that John Madden Football finally came out for the Apple II in 1988, four other football games had already come out: Tecmo Bowl, 10-Yard Fight, 4th & Inches and TV Sports: Football. None of these games featured the realism of EA’s creation, but as it turned out, that might actually have been to their benefit.

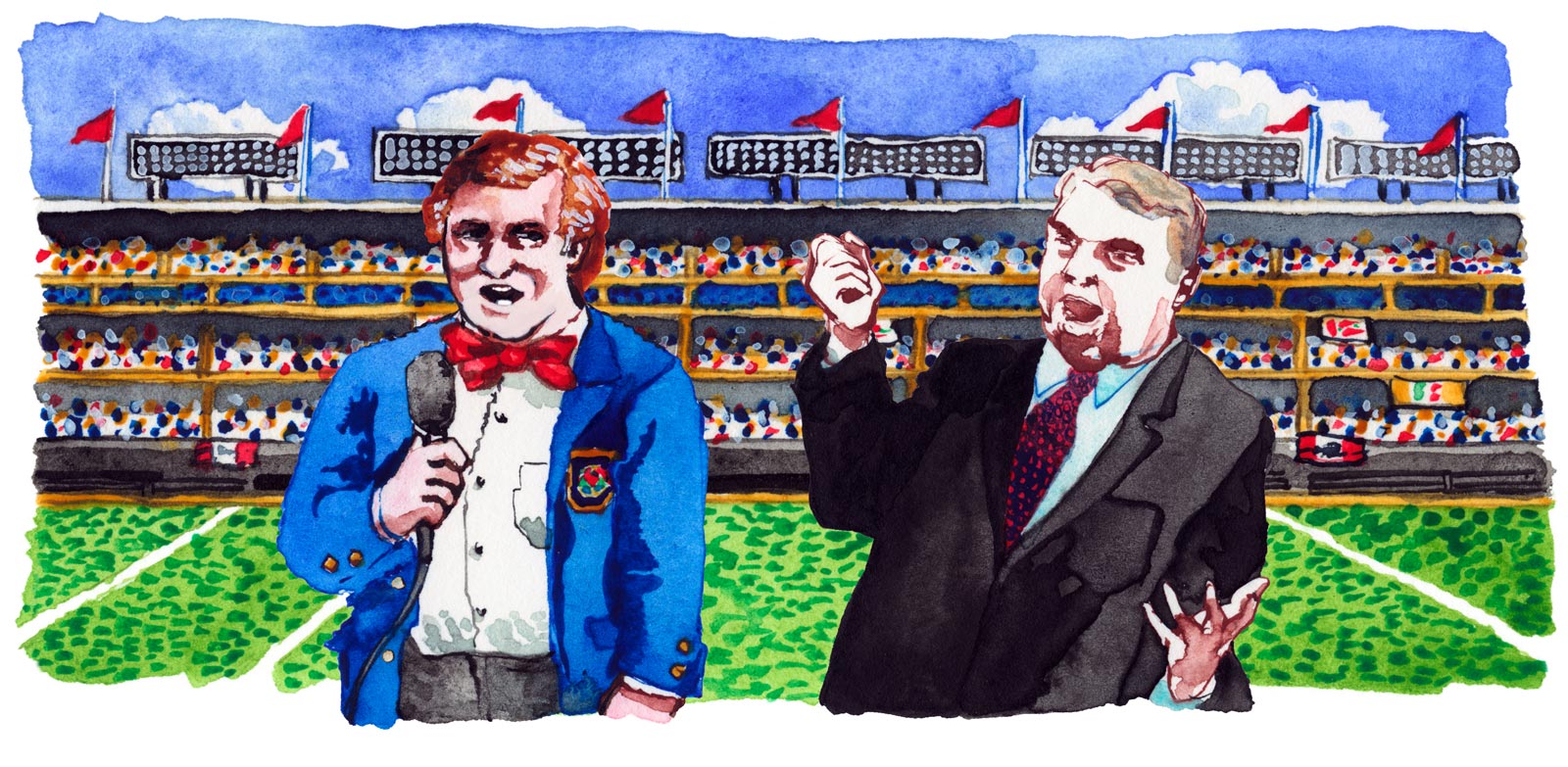

EA had John Madden, but Cinemaware’s TV Sports: Football for MS-DOS seemed to have something even better: Don Badden, a hefty commentator with a cherubic face and sandy, sloping hair. How could a cheeky, cheesy, doppelganger possibly be better than the real thing? Because, well, sometimes facts just can’t compete with fiction; an approximation of actuality can often feel more honest than the truth. And, in the end, as ‘realistic’ as John Madden Football turned out to be – with all those plays, players, and statistics – it just wasn’t very fun.

This was a problem but, as fate would have it, one that turned out to contain the solution.

Building a Hotel on Park Place

Not long after the success of TV Sports: Football, a software engineer named Michael Knox left Cinemaware. In 1989, he founded a development company called Park Place Productions, with his high school friend and fellow software engineer Troy Lyndon. Their first release was ABC Monday Night Football, which ably followed in the footsteps of fun-first, arcade-style football games.

Meanwhile, things at EA had started to turn around. The company went public in the fall of 1989 and Hawkins started to amend his anti-console stance. He still didn’t like the idea of doing business with Nintendo, but he was willing to work with their competitor Sega, who boasted a technologically superior 16-bit system – the Genesis.

EA had gained enormous leverage with Sega by reverse-engineering their technology, and after the pair struck a sweetheart deal, EA made a concerted effort to produce more games than ever before. Hawkins wanted the company to triple the number of titles they put into production each month and re-establish themselves in the category of sports. So EA created a new basketball game, Lakers vs. Celtics and the NBA Playoffs, a new golf game, PGA Tour Golf, and began developing a console-version of Earl Weaver Baseball. But what about football? Could John Madden Football really compete with all those arcade-style football games? Hawkins wasn’t sure, but commissioned Robin Antonick to begin building a version for the Genesis.

In the meantime, he met with Knox and Lyndon to explore the idea of simultaneously developing another football game. They hit it off and in March 1990, EA paid Park Place Productions $100,000 to produce something faster, feistier and more arcade-style (less Madden, more Badden). To program this new football title, Knox and Lyndon turned to another high school friend: Jim Simmons, a former college drop-out who had never professionally programmed a game before.

The Chosen One

‘We need someone who really understands sports,’ Trip Hawkins explained over the phone to Michael Brook, still in Amsterdam. ‘Someone who really understands sports, but is also into games. Would you be interested?’

Although long-distance calls can often quiver with a distant dreamlike quality, Hawkins’ hyper-present personality made this one sound like he was standing right there with Brook, arm around him, coaxing him to return to the mothership. Who could possibly resist charisma like that? And so in May 1990, Michael Brook re-joined Electronic Arts.

Brook’s first project was the as-yet-untitled arcade-style football game, for which he’d serve as the associate producer. His first day back entailed a quick trip down to San Diego with producer Rich Hilleman, to visit Park Place’s office and see what was going on with this new game. More specifically, they wanted to check on Jim Simmons, the enigmatic twenty-two-year-old programmer who had as many college diplomas as he did professional credits: zero. Actually that’s not true. Although Jim had never coded a game before, he’d been the audio technician on TV Sports: Football and received an audio conversion credit on Cinemaware’s Rocket Ranger.

‘What’s Rocket Ranger?’ Brook jokingly asked.

‘What’s an audio conversion credit?’ Hilleman replied.

The trip went from ominous to curious when the pair were picked up at the airport by a limo with their host Michael Knox in the driver seat. He explained that no-don’t-worry he didn’t moonlight as a chauffeur, it’s just that he and Troy Lyndon owned this limo but they just didn’t have a driver at the moment so … yeah. To avoid prolonging the awkward moment, Brook and Hilleman got in the car and they all made their way to Park Place.

If any doubts about returning to EA had started to creep into Michael Brook’s mind, they vanished upon seeing Jim Simmons’ work. Wow, just wow. Although at this point there weren’t any plays or structure to the game – it was essentially just 22 guys chaotically running around on a football field – the chaos that Brook and Hilleman witnessed was beautiful. The field resembled a cartoon and the players were merely caricatures, but there was a fluidity to the way they moved and a logic to the physics of this pixelated universe that captured the essence of football. This game was going to be great, Brook thought, it’d be goddamn groundbreaking and even crush the John Madden Football game that EA had in simultaneous development.

And it did end up doing all this, but not quite in the way he had imagined.

What’s in a Name?

With Simmons’ game showing potential to become a hit, EA decided to scrap Robin Antonick’s John Madden Football. But rather than write off Madden’s hefty prepaid royalties, EA decided to slap his name on the Park Place project instead. And so, for purely financial reasons, the project that EA had developed as its anti-Madden football game wound up becoming the iconic John Madden Football.

Electronic Arts were confident they had scored a touchdown with John Madden Football, but the scale of its success went beyond anything they had anticipated. They had agreed to increase Madden’s royalty rate, as they expected to sell 75,000 units. In reality, however, it ended up selling about 400,000 units for the Genesis, greatly boosting Sega’s new 16-bit console and almost single-handedly fulfilling EA’s desire to become the videogame industry’s flagship sports game-maker.

On the back of this triumph, Brook and Hilleman decided that what they ought to do next was a hockey game. To replicate the magic of Madden, they followed a similar recipe: Park Place was hired to develop the game, Jim Simmons was tasked to program it, and while gameplay nuances (penalties, playbooks, player ratings and the like) were to be given the royal treatment, arcade-style fun was to reign as king.

But as successful as the Madden experience had been, there were many things that Brook and Hilleman wished to improve upon. For example, due to a Genesis cartridge’s tight ROM restrictions, John Madden Football players could only pick from 16 different teams, although the NFL actually had 28 at the time. And because EA hadn’t reached a licensing deal with the NFL, they weren’t allowed to use any team names or logos. This meant that instead of the San Francisco 49ers, players were simply offered a team called ‘San Francisco’, whose red and gold color scheme just happened to match that of the 49ers. The same principle applied when it came to the players: since no deal had been struck with the Players Association, Joe Montana couldn’t officially take the digital field as San Francisco’s quarterback; instead that honor would go to someone who looked, moved and threw like Montana, but simply went by the moniker ‘#16’. Most of this namelessness was a symptom of the times (this just wasn’t done in games of the era), and part of it was a matter of financial priority, but the stage was set for a change. It wouldn’t be possible much longer for game developers and sports leagues to ignore the mutual financial benefits that official licensing would bring.

Up until this point, EA had demonstrated a willingness to open their wallet for individual celebrities (see: Larry Bird, Earl Weaver and John Madden) but not an entire sport. This was where Brook and Hilleman saw an opportunity. In their minds, the videogame was the star; not the athlete or coach smiling on the cover. No longer interested in working with MVPs like Mark Messier, Wayne Gretzky or Mario Lemieux (who Sega signed for their own hockey title), they instead targeted the NHL and the NHLPA. Rebuffed by the NHLPA, EA happily struck a deal with the NHL for 1991’s groundbreaking NHL Hockey, which went on to hit the back of the net, selling in six-figure numbers, just like its football sibling.

Sequels

After NHL Hockey was finished, the company quickly got to work on a follow-up to John Madden Football. Its working title, John Madden Football 2, might not sound risqué to modern ears. But in 1992, it caused a significant question to ring through the halls of EA; a question whose answer, at the time, was by no means assured:

‘Will people actually buy the same game a year later?’

Although sequels in the videogame world had a very strong track record, internal skepticism stemmed from the opinion that Madden 2 wasn’t quite a sequel. Unlike Super Mario Bros. 2, Mega Man 2 or Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, this wasn’t going to be about loveable characters returning for a brand new adventure. No, this was going to be the same, visually-identical players returning to play the same sport, whose rules had not changed in the past year. Who would cough up another fifty bucks for that?

Brook, however, knew that sports fans experience their passion through the annual incarnation of their favourite team. In a football fan’s mind, the ’92 49ers were a completely different entity to the ’91 49ers; so EA’s new football game should embrace these seasonal nuances, even reflect them in its title: John Madden Football ’92. Last year’s game would be so last season.

Just as the football fan distinguished the ’92 49ers from the ’91 49ers by the 92 team’s addition of quarterback Steve Young, so the gamer would distinguish each new version of Madden by its inclusion of a major change – a ‘killer feature’. In John Madden Football ’92 that killer feature would be an instant replay function, topping off a multitude of other innovations such as new formations, variable weather conditions and bone-crunching injuries that would require an ambulance to zip onto the field.

Implementing these upgrades once again fell upon the shoulders of Jim Simmons, but this time EA cut out the middleman. They hired Simmons, and stopped working with Park Place. Who needs the golden goosery when you’ve already got the golden goose?

John Madden Football ’92 came out in November 1991, three months after NHL Hockey had hit the shelves, and both games were such resounding successes that new versions for the following year were immediately put into development. Although Brook had been back at Electronic Arts for less than two years, he was well on his way to discovering the most valuable commodity in the videogame industry: a franchise.

The Dangers of Making Wayne Gretzky Bleed

There was, however, one not-so-tiny hitch…

A couple of months before NHL Hockey was due to hit stores, Brook was at the Stanley Cup Finals in Pittsburgh to show off his soon-to-be-released game. The NHL provided him with a couple of large television monitors and set them up in the arena’s hospitality center for what amounted to a public unveiling of NHL Hockey to players on hand, assorted bigwigs and members of the media.

‘Amazing!’

‘It looks so real!’

‘This is the best hockey game I’ve ever played!’

For most of the evening, that’s all Brook heard. EA had done it again. As if this wasn’t enough, John Ziegler – the NHL’s commissioner – was sitting only one table away, hearing each and every compliment. The producer from EA was floating on cloud nine – until a nearby exclamation rained on his parade.

‘I just got Gretzky in a fight!’

Brook felt the force of the sucker punch. It took a second for the rest of the room to register the statement. As it sunk in, VIPs gathered around the monitor to watch Wayne Gretzky, the face of the NHL, get into a fistfight with an opposing player. And as the pixelated version of hockey’s greatest player spilled blood onto the ice, everyone’s eyes darted to John Ziegler, anxious to gauge the commissioner’s reaction.

In the moment, Ziegler played it close to his chest, but afterwards he was furious. Fighting had always been part of the sport – a means for players to police themselves – but it had recently become such a hot-button issue that the league had considered banning it once and for all. The last thing the league wanted was a videogame that glorified fighting. And in real hockey, it was only the enforcers who fought with one another, so why the hell did this videogame allow for Wayne Gretzky to get beaten up? Under no circumstances should that face be bloodied, bruised or rendered black and blue. This was unacceptable, a deal-breaker, and so the NHL demanded that EA remove the feature.

However, although the game wouldn’t come out for another couple of months, the final code had already been shipped to Japan: millions of cartridges were in the process of being manufactured, and a freight of boats had been chartered to bring back the complete games. These facts were made clear to the NHL, who sympathised with EA’s difficult situation, but were now unwilling to change their stance: do not ship this game … or else.

Or else what? Brook wondered, and soon got his answer in the form of an ultimatum: if EA released NHL Hockey as it was, then the NHL would not work with them on future games. That meant no logos, no team names, and no more Stanley Cup invitations. Brook spent the next few days surveying customers and the consensus was clear: they’d rather have fighting than logos. And so, after making the best hockey game to date, EA and the NHL parted ways.

Power to the Players

There aren’t too many people who find themselves able to stick it to a multi-billion dollar sports league, but in 1992 Bob Goodenow was in this exclusive minority.

Goodenow was a former agent who, at the start of the year, had become the NHLPA’s executive director. He walked into a minefield, as the league’s collective agreement had expired just before the season, and he spent his early days negotiating with John Ziegler. Needless to say, the sides did not see eye to eye (the players would end up going on strike that April), but this stood in EA’s favour. Michael Brook flew up to meet Goodenow at the NHLPA’s headquarters in Toronto, confident of striking a deal.

‘We’ll give you the license,’ Goodenow said, ‘Just make the fighting realistic.’

Brook agreed and NHLPA Hockey ’93 was born. Jim Simmons tinkered with the parameters of his tiny hockey universe to create an environment in which there were only 1.2 fights per game (close to the NHL’s actual figure of 1.05), which were fought, primarily, only between each team’s enforcers. As for the skirmishes themselves, Brook and Simmons did a brilliant job of upgrading the game’s fighting engine. With high punches, low blows, and the ability to move from side-to-side, there was an art to winning these feuds that went beyond simple button-mashing.

The improved fighting feature was certainly a fan favorite (see: Swingers), as was the addition of in-game analyst Ron Barr, but for all the game’s harder hits and faster slap shots, there was no true killer feature. Even on the back of the game’s box, it’s clear that EA’s copywriter was scraping the bottom of the barrel, emphasising ‘battery backup,’ ‘player injuries’ and ‘highlights from other playoff games.’ Yup, that’s right, players could now watch fictional highlights from fictional games.

Yet despite the lack of innovation, NHLPA ’93 Hockey was still a terrific game. Its predecessors were infinitely playable experiences that mixed in just the right amount of realism, and this one was bigger, faster and – of course – bang up to date. There was one other factor strongly in the game’s favor: lack of competition. But that would soon change, as would the team behind EA’s now-annual hockey franchise.

Lesser Is More

Three contenders for the 16-bit hockey cup were about to take to the ice: NHL Stanley Cup, Pro Sports Hockey and Brett Hull Hockey were all slated for a release in 1993, but it wasn’t just a crowded marketplace that prompted EA to re-evaluate the direction of their budding sports empire.

The most significant change EA made was with Jim Simmons, the prodigious programmer behind their flagship sports titles. Instead of using his powers to annually upgrade the football and hockey franchises, he was to build them another world. This time with soccer.

Simmons’ replacement, Mark Lesser, was just about as seasoned as one could be in the nascent videogames industry. In the 1970’s, he had specialised in designing the tiny chips inside of handheld calculators, and when Mattel Electronics came up with the wild idea of reconfiguring handheld calculators into portable videogames, he had designed five of the toy company’s first handheld games, including Auto Race, Brain Baffler and, most famously, Mattel Electronics’ Football. EA found Lesser’s makeup appealing, and poached him from a sub-contractor after he completed programming Madden ’93. But little did they know, Lesser had a dirty little secret: he’d never once watched a game of hockey in his life.

NHL ‘94

In Lesser’s defense, he wasn’t all that big a football fan either, and look how well that had worked out with Madden ‘93. In fact, Lesser genuinely believed that a complete outsider mentality would be one of his greatest assets when reshaping the franchise. With his lack of familiarity, he would see things – both in Simmons’ game and the sport itself – that others no longer noticed. His ignorance would make him more attuned to the minutiae of hockey, and with enough expert tweaks to these tiny moving parts, he would start to effect substantial changes to the whole mechanism. And there was one more advantage, he thought, to approaching something with a naïve point of view: wonderment, a sensibility he hoped to stitch through the game.

The official passing of the baton took place at EA’s office in San Mateo, where Lesser met with Jim Simmons, Michael Brook and a producer named Scott Orr who had worked with Lesser on Madden ’93. There, Lesser and Simmons talked a little about programming – garnering glazed eyes from the others as they spoke code – and then spent most of the meeting discussing innovations for the new game.

At the top of Brook’s wish list were shoot-outs, goalie control and one-timers (a type of shot where the player simultaneously receives a pass and shoots the puck in one swift, fluid motion). That last one, the one-timers, was the most important of all; another nuance specific to hockey that would add realism and could be calibrated for fun. Lesser nodded a lot; it all seemed to make sense and appeared to be doable. He didn’t know what half of the hockey terms they were talking about meant, but he assumed that he would figure them out and be able to code them.

After the meeting, Lesser went back to his cabin in Maine. That’s where he thought best, and that’s where he would be doing the majority of his work on the game. His next milestone was to deliver a technical design document to EA, but before committing himself to the language of code, he needed to get a crash course in hockey vernacular.

His mentor during this time was Shawn Walsh, head coach for the University of Maine’s hockey team. Walsh was something of a local legend: the fiery coach who turned an obscure college program into a perennial powerhouse. Lesser attended practices, studied the playbook and had long conversations with the coach; anything, really, to see the sport through his eyes. And what he picked up was a revelation that probably would have made Ken Baumgartner want to punch him in the face: so much of the sport came down to awareness. At any given time, there were a dozen cues that a player had to focus on (angles, alignments, trajectories, etc.) that dictated their own behavior as well as that of the team, and that awareness was ultimately what he needed to capture through code.

Meanwhile, Brook became reluctantly aware that at some point he’d need to make peace with the NHL. Not having the realism afforded by an NHL license represented a minor embarrassment for EA (especially when competing hockey games had started to secure the license), but more than that, Brook sensed a shift coming to the industry: a move from cartridges to CDs; and when this evolution was complete, EA would need to include game footage in their releases. Unsurprisingly, every single second of game footage was owned by the NHL. For this reason, discussions were once again opened up between EA and the NHL and then for the same reason as before – fighting – those discussions went nowhere. The league still wasn’t willing to bend on this issue.

Screw it. EA had released a bestseller without the league once before, and they would just have to do so again. Even without featuring logos and teams from the NHL, Brook thought, there were other ways to improve the realism of this game. For example, it could emulate the ambience of a game day NHL arena by including the proper organ music. The problem, though, was that each team’s organist played different songs. ‘That’s not a problem, actually,’ explained Dieter Ruehle, the organist for the San Jose Sharks (and previously for the Los Angeles Kings), ‘I can do that.’ True to his word, Ruehle provided EA with organ music for every team; and he didn’t just provide all of their songs, but also noted which music was blasted during power plays, which tunes were used to celebrate goals, and all the other inside info needed to make each arena feel like home. Ruehle was so diligent about getting it right and capturing that home crowd essence, that during a recording session at EA’s sound studio he asked:

‘The woman who plays the organ for the Washington Capitals has arthritis; would you like me to play the songs how they are meant to be played, or the way that she plays them because of her condition?’

‘Definitely the way she plays it!’ Brook answered, after a laugh.

Igor Kuperman & The Quest For Authenticity

As the deadline for finishing NHL ‘94 approached, the NHL continued to stonewall Michael Brook. Once again, it came down to a simple choice: in-game fighting or an NHL license. This time, however, Brook opted to work with the league. The shift to CD had begun: with the release of the Sega CD and 3DO’s 32-bit console, he could see that the wind was now blowing strongly in the direction of full-motion video and ultra-realistic graphics. Although he knew that removing fighting would disappoint some gamers in the short term, Brook believed that EA would need the NHL onside for future games; and so, just a couple of weeks before the game was finished, he let his programmer know that fighting needed to be removed from the game. Lesser did so without complaint, but still Brook felt bad. The game wouldn’t be everything he wanted it to be, everything it should be, and that was always a tough reality to face. But when the business or politics of development got to him, he found tranquility in reminding himself how far he had come.

These games were resonating not only with a generation of sports fans, but also with the players themselves (see: Ken Baumgartner) and sometimes even their spouses. On one occasion, after shipping one of the Madden games, Brook received a call from the wife of San Francisco 49ers cornerback Eric Davis. She didn’t understand why her husband’s rating was so low and why he wasn’t featured in the starting lineup because, as she made very clear, he was a starter. Brook, who had done all the ratings himself, had to explain that the lineups (and ratings) were made before the season started, so congratulations to her husband for moving up the depth chart, but her husband’s depiction in the game was based on all the available information at the time. She was still not satisfied and hung up. A couple of minutes later, Eric Davis’ agent called and Brook had the same conversation with him.

Brook wasn’t the only one who had these experiences – almost every employee at EA during this era had a similar rating-related brush with fame – and John Madden himself got the worst of it. He’d walk through locker rooms and get chided or commended from players he’d never met before based on how they had been rated; all of this despite the fact that he hadn’t been directly involved with any aspect of the 1990 Genesis game that launched the franchise.

With incidents like these becoming commonplace, eventually it made sense to bring in professional scouts. For the football games, Jon Madden’s sons Joe and Mike were responsible for the player ratings and for the hockey games, EA hired Igor Kuperman, a scout for the Winnipeg Jets. Prior to working for the Jets, Kuperman had been a sportswriter in the Soviet Union which, during an influx of Eastern Europeans into the NHL, gave him, and EA, intimate knowledge of players whose names most analysts couldn’t even pronounce. Details like these demonstrated EA’s compulsion for authenticity, but even as technology enabled art more easily to imitate life, there were still limits to what could and should be done.

‘What about referees?’ Lesser asked over the phone.

‘What about them?’ Brook replied.

‘In every hockey game there are two linesmen,’ Lesser explained, ‘but we don’t show them in the game.’

This is because referees would have been distracting. And this, perhaps, is the best example of what EA’s early sports games were all about. Yes, it would have been more accurate to have referees on the ice, but that wouldn’t have made it more authentic. Accuracy is a binary, it’s measurable; it’s either correct or it’s not. But authenticity, that’s a whole other story. It takes into account emotion, perception and the greyness of facts: it’s something elusive and essential. This was what EA wanted to give their customers, and it’s what made perfecting the one-timer so damn hard.

After much struggle, Mark Lesser had finally figured out how to build one-timers into the game, but he wasn’t feeling good about his solution. What he had created in the game was technically correct: it matched the physics of what he’d seen at the practices, on the ice and in the videos he watched in slow motion. But, still, it didn’t feel right. It was accurate, but it wasn’t authentic, and that kept him going. He couldn’t describe what exactly he was looking for, or say for sure that such a feeling existed, but he kept on at it until one night, at two in the morning, he found what he was looking for. It just felt right; perfect really, like a spring being compressed and then let free. And feeling like a kid who’d made it to the end of a rainbow, or like an adult who realised how much he loved his job, he jumped up and down, so excited and pleased.

Technically, he was alone in a barn in the middle of the night in Maine. But that, really, wouldn’t be an accurate way to describe the situation. Because, in that instant, what he felt was the essence of hockey, the authenticity of videogames and the momentary company of the millions who would one day play and fall in love with NHL ’94.