Arcade Perfect

How Sega brought the Mega Drive into the mainstream

It was the first week of September 1990 when the commercials hit American TV. The Sega Genesis had been out in the country for a year, quietly building a fan base with slick arcade conversions like Altered Beast and Golden Axe. With its 16-bit credentials stamped on its casing like a muscle-car badge, it was the most powerful console on the market, and had the potential to reshape gaming in its own, sleek image. But first it would have to defeat the competition. And that meant having to take out Nintendo.

But Nintendo was Goliath. The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was the biggest game console on the planet. Thirty million American households owned one and they were so prevalent that the word ‘Nintendo’ was synonymous with the medium. You didn’t play video games … you played Nintendo. Sega was nowhere. Its Master System – designed to compete with the NES – had barely made a dent. ‘We officially claimed that Sega had 10% market share and that Nintendo had 90%,’ recalls Shinobu Toyoda, who joined Sega of America in 1989 as executive vice president, having been hand-picked by Sega president Hayao Nakayama to be second in command. ‘The truth was, Nintendo had 94% market share with their NES system. Sega had only six.’

But Nintendo’s dominance didn’t deter Michael Katz. The president of Sega of America harboured grand ambitions. He’d been approached by founder and chairman David Rosen to establish the company’s corporate presence in America, where it had barely 40 employees – most of them in marketing and customer support. There was no real autonomy, no identity. Taking up his new position a month after the US launch of the Genesis, Katz set his sights on grabbing half the console market share … as a minimum. The battleground had to be North America.

‘We had to create awareness, to make a noise and grab attention. After all, we had nothing to lose – by then we had a 2% share of the market! But I had to fight with David Rosen and the ad agency and instruct them to do competitive commercials. They were showing me all these storyboards and concepts that had nothing to do with Nintendo. I learned that it was considered inappropriate in Japan to do competitive advertising – to publicly tear down a competitor. But the rule of thumb in consumer marketing is that if you’re number two and less well known, but you have better features, you go after your rival.’

And that’s exactly what happened. In September 1990, a TV ad was screened coast to coast, showing clips of Super Monaco GP, Joe Montana Football and Moonwalker, the voiceover proclaiming the awesome power of the new machine. Katz set out his stall in style: the Genesis represented the birth of a powerful new vision of gaming, so it didn’t need to compete directly with the outdated NES; the console had its own, original games that gave modern gamers something different. And this message was encapsulated perfectly by the ad’s ending – a single slogan suggested in a meeting one afternoon by a copywriter at Bozell, a slogan that would resonate throughout the ’90s and fundamentally alter game industry sensibilities: ‘Genesis does what Nintendon’t’. It was brilliant – provocative, feisty, irreverent – and it laid down the gauntlet. But it wasn’t just about the technology, it was about attitude – Sega wasn’t Nintendo, and it didn’t want to be. Nintendo didn’t do licensed sports sims. Nintendo didn’t do violence. Nintendo didn’t have Michael Jackson. Sega did. This first TV ad was the opening salvo in Sega’s battle with Nintendo, and it made it abundantly clear that the Genesis was moving the goalposts. ‘With this kind of advertising, you need the ammunition,’ says Katz.

With the strategy in place, what Sega needed was an icon that embodied its bold new values, one that could go head-to-head with the likes of Nintendo’s world-conquering Mario and put clear blue water between it and its rivals. That icon – who would come to exemplify the Mega Drive’s particular blend of attitude and bravado – was Sonic the Hedgehog. The origin story is the stuff of legend. With the Super Nintendo launch looming, Phantasy Star veteran Naoto Ohshima had already started work on an offbeat animal character with programmer Yuji Naka. ‘We initially chose a rabbit … and then experimented with further ideas – an armadillo and a hedgehog,’ says Naka. ‘Ohshima-san’s hedgehog illustration was very stylish and best represented the speedy qualities we were looking for.’ Sega management went for it and the character evolved, taking aspects from manga as well as Western cartoon characters like Fritz the Cat and Mickey Mouse. Sonic’s blue colouring matched the Sega logo, but along with his fiery red trainers and big white eyes, the final design also made subtle reference to the US flag.

Ohshima-san’s hedgehog illustration was very stylish and best represented the speedy qualities we were looking for.

But the speed – Sonic’s defining characteristic – came from Naka. An accomplished programmer and avid motorsport fan, Yuji Naka also understood the strengths of the Mega Drive hardware, utilising these skills to accelerate the animation to a lightning-fast pace. Working alongside Ohshima, Naka’s initial vision was for an action game in which players traversed through the game world in a similar way to his recently completed Ghouls’n Ghosts, but sped up. ‘So the very first part of the program that I finished,’ says Naka, ‘was the smooth, high-speed running action that later became the most iconic aspect of the Sonic games.’

Hirokazu Yasuhara came in to lead the team, and introduced the concept of a pinball table environment – the perfect landscape to indulge Sonic’s incredible velocity. The game unwittingly encapsulated Sega’s emerging message: punchy visuals, impatience, speed. Sonic even tapped his foot and crossed his arms in exasperation whenever the player dared to stop. Sonic was all about motion, and he embodied everything that was so exciting about 16-bit gaming.

But it didn’t come together at once. When early versions of the code made it across to the US, development staff were initially sceptical. ‘One day we got this … I guess you’d call it an alpha copy of a game named Sonic,’ says Craig Stitt, an artist who joined Sega Technical Institute – the company’s Palo Alto-based studio – just as work was beginning on Chameleon Kid/Kid Chameleon. He recalls:

‘We’d never heard of it. We went into the game room, stuck it in, played it, and it really wasn’t very fun. It was beautiful, but you ran around for a few minutes and then you handed the controller off to somebody else and went back to work. A month or two later, we got what I’m assuming was the beta version. In this one, when Sonic got hit, the rings flew and scattered. The game became addictive. Suddenly you couldn’t stop playing. You were fighting over who got the controller. It made that much difference!’

Katz remained unconvinced, even to the end. ‘When we heard the Japanese were developing a game based on a hedgehog we almost croaked,’ he laughs. ‘Nobody even knew what a hedgehog was!’ Katz wasn’t around long enough to find out. Although he had laid the foundations for the US success of the Genesis, Nakayama wasn’t happy with his progress. Katz explains:

‘Japan didn’t understand how long it would take to build market share. The mantra they had for me was “Hyakumandai”, which meant one million units. I was supposed to wake up every morning and say that to myself. They thought a million units should be achievable in the first 12 months. We managed 500,000, which was damn good considering we didn’t have our own development staff and hadn’t yet released many of the original games under the licences we had worked so hard to secure. I don’t believe in kissing the butts of the people I work for. I believe in setting my own goals. But they got impatient.’

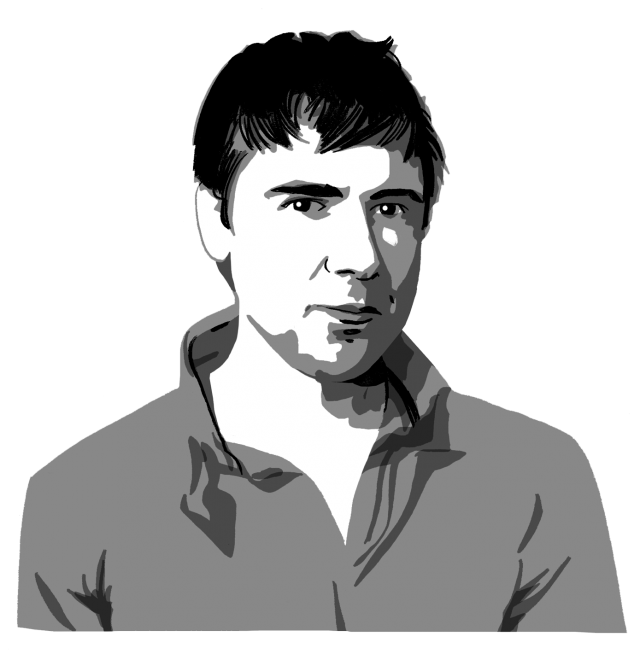

Nakayama wanted Katz out, and as a replacement he had his eye on Tom Kalinske, an ex-Mattel president who had just helped buy out the Matchbox toy firm. ‘I’d actually met Nakayama when I was at Mattel,’ explains Kalinske. ‘We would go over to Japan and talk about licensing some of Sega’s arcade characters for our products. One day Nakayama called me and said, “Hey, I’m distributing my 8-bit system in the US through Tonka Toys and I’m not really happy with how they’re doing it – would Matchbox like to take it over?” I looked at the system and compared it to the NES, and I didn’t see any possibility of it succeeding so I turned it down.’

But Nakayama eventually got his man, though his approach was unconventional. ‘Years later, we ended up selling Matchbox to Tyco so I had just left the company and was on vacation in Hawaii with my wife and children,’ says Kalinske. ‘We were on the beach one day and all of a sudden this shadow appeared over me. And it was Nakayama – he had literally stalked me! He had tracked me down through my secretary and flown over. He said, “You’ve got to come back to Japan with me.” I said, “Are you out of your mind? I’m on vacation!” He said, “No, I’ve got some cool stuff to show you, you’re going to love it – it’s 16-bit technology.”’ All the while, Kalinske’s wife and children were listening in on the conversation. ‘I asked them what I should do, and my youngest daughter said, “Well, this man says it’s really great, so you better go, Daddy!”’

We were on the beach one day and all of a sudden this shadow appeared over me. And it was Nakayama – he had literally stalked me!

And go he did. In the autumn of 1990, Kalinske took over as CEO of Sega of America, and instantly began work on consolidating the new philosophy: that the Genesis was the machine that kids graduated to when they found the NES too limiting. ‘The starting point,’ says Kalinske, ‘was that Nintendo was clearly the preference of the child gamer. To me, it seemed logical to really hammer the older audience, and to do that with more aggressive marketing, and with sports, strategy and role-playing games that appealed to teenagers and college-age males.’ Toyoda recalls the same thought process. ‘Tom knew that our audiences were getting older, it was no longer young kids,’ he says. ‘So our content had to grow up a little to meet this more mature market. Not the mature of today’s gamer – not 35-year-olds – but Nintendo was strong on 6–11-year-olds, so Sega had to go after the 12–18 age group. That was mature.’

Like Katz, Kalinske knew the company needed a mascot to lead its software line-up. Unlike Katz, however, Kalinske understood the Sonic concept. ‘Katz hated Sonic,’ he laughs. ‘I think there’s some memo on file somewhere – he didn’t want anything to do with it. I was a little more pragmatic about it. I thought it showed off the attributes of 16-bit very well – the speed of movement and the colourful graphics. Then our marketing team did a bunch of revisions on the original Japanese character design so that it was acceptable for the US market. We got rid of the fangs and the aggression, and we added the red shoes’ – an alteration that Ohshima also claims credit for. ‘He had a girlfriend named Madonna with this great cleavage. We got rid of her too.’

But Kalinske still needed to be convinced of Sonic’s appeal. ‘I don’t always rely on research,’ he says, ‘but I wanted some evidence that we weren’t going to fail with this character.’ So he called in Al Nilsen, the global head of marketing, who was convinced by Sonic. ‘I knew ahead of time we had our Mario killer,’ says Nilsen. ‘Tom Kalinske said, “Prove it to me before we go public on this thing.” So we went and did research, we playtested across the country with ardent Mario lovers – they worshipped Mario, he could do no wrong. We showed them the new Mario and then we let them play Sonic. Of these confirmed Mario fans, 80% choose Sonic. It was like … “Wow!”’

Kalinske was sold. The marketing ramped up and Sonic went live at the 1991 Summer Consumer Electronics Show, the same event at which Nintendo revealed the SNES to the US. As Nilsen recalls:

‘On the first day after the Nintendo press conference, a reporter from a major national magazine came over to me and said, “The Super Nintendo has 32,768 colours – you only have 512. What are you going to do about it?” I just got him to follow me to our booth, showed him Sonic and Mario running side by side and said, “Okay, which one has the most colours? It’s not how many colours you have, it’s what you do with them.” The reporter just walked away.’

Released in the US on 23 June – a full month before its launch in Japan – Sonic was a smash. Everyone understood that this was something new and important. ‘Sonic has thrown down the gauntlet to Mario in a big way,’ wrote C+VG magazine in its ecstatic review. ‘Everyone’s favourite Italian plumber must be feeling just a little washed out.’ Inspired, Kalinske went over to Sega of Japan and announced his plan to bundle Sonic with the Genesis, while reducing the price of the console to $149. He saw this as the perfect way to detract attention from the US launch of the SNES and secure more precious market share.

The response was explosive. ‘The Japanese board thought I was nuts,’ says Kalinske. ‘They said, “My God, we don’t make any money on the hardware as it is. If we give away the best title, you’re taking the software profit away. It’s crazy!”’ But Nakayama remembers the ambition of Kalinske’s proposition. ‘At that time the software buying rate in the US was, on average, three games to one piece of hardware,’ he says. ‘But Sega of America believed that even if we sold the unit with Sonic under cost price, they could cover the loss and make a profit on future sales of software.’ It was the loss-leader philosophy taken to its very extreme.

The Japanese board thought I was nuts. They said, ‘My God, we don’t make any money on the hardware as it is. If we give away the best title, you’re taking the software profit away. It’s crazy!’

The room descended into chaos. But Kalinske stuck to his guns:

‘The board members were all talking in Japanese. Toyoda was trying to translate for me as fast as he could, but he couldn’t keep up with all the banter going on. And then Nakayama got up and kicked a chair over … He was angry that everyone else in the room was so negative at what I was proposing. At the end of the meeting, as Nakayama was walking out of the door, he turned and said to everybody, “I don’t care what you say. I hired this guy to make changes in the US. I promised him a free hand, so we’re going along with him.” He was very clear. He might have been surprised at the things I wanted to do, but he wasn’t angry at me. Nakayama overruled them all. And that was the end of the meeting.’

The decision resulted in a huge boost in Genesis sales, with 15 million units of the Sonic bundle being sold. The Genesis, with Sonic leading the charge, hadn’t just captured the teenage market, it had captured the zeitgeist. The machine was speaking to a generation that had grown up with MTV, a generation raised on jump cuts and dislocated narratives. This was the era of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Garbage Pail Kids, of casual surreality and postmodern mania. For these kids, the Genesis was now an aspirational product that measured up to the teen generation’s universal yardstick – it was cool.