A Brief History of Speedrunning

How Doom and Zelda became stages for an exhilarating internet subculture

Of all the iD Software games from the early ’90s, I only hazily remember Wolfenstein 3D at best. My mother’s big beige block PC in her upstairs office had it installed. It was an otherwise cramped room: stacked with papers and behavioural therapy workbooks from her private practice, all nestled next to romance novels and the DSM-IV. There was also Billy the Kid up there, and Commander Keen in Aliens Ate My Babysitter. There was Minesweeper of course, which I never got the hang of, and Solitaire, which I managed to beat once or twice before the age of 10. More importantly, her office housed a modem, and the small mechanical fan next to her desk was always on to keep her computer setup cool in those damp, muggy, Virginia summers. The fan would turn its head disapprovingly back and forth as I logged on to play videogames during summer break. My memories of gaming in my early childhood are always accompanied by the sound of a whirring fan.

I’m not going to pretend I remember the specs of her computer, or even exactly what year it was. I remember shooting Nazis in the face, I remember William Joseph ‘B.J.’ Blazkowicz’s eyes and jaw moving back and forth in the HUD, and the way his face got bloodied as his health trickled down to zero. It wasn’t a game to win in the traditional sense of the word. At least, not to me. Wolfenstein 3D was a collection of inputs and responses: collecting turkey dinners and gliding through cyan doors. I’d stare at the box art for the game, as punchy and pulpy as any Johanna Lindsey novel on my mother’s bookshelf. My recollections of these iD Software titles – lacking in plot, but rich in colour – seem to hold up fine against the test of time.

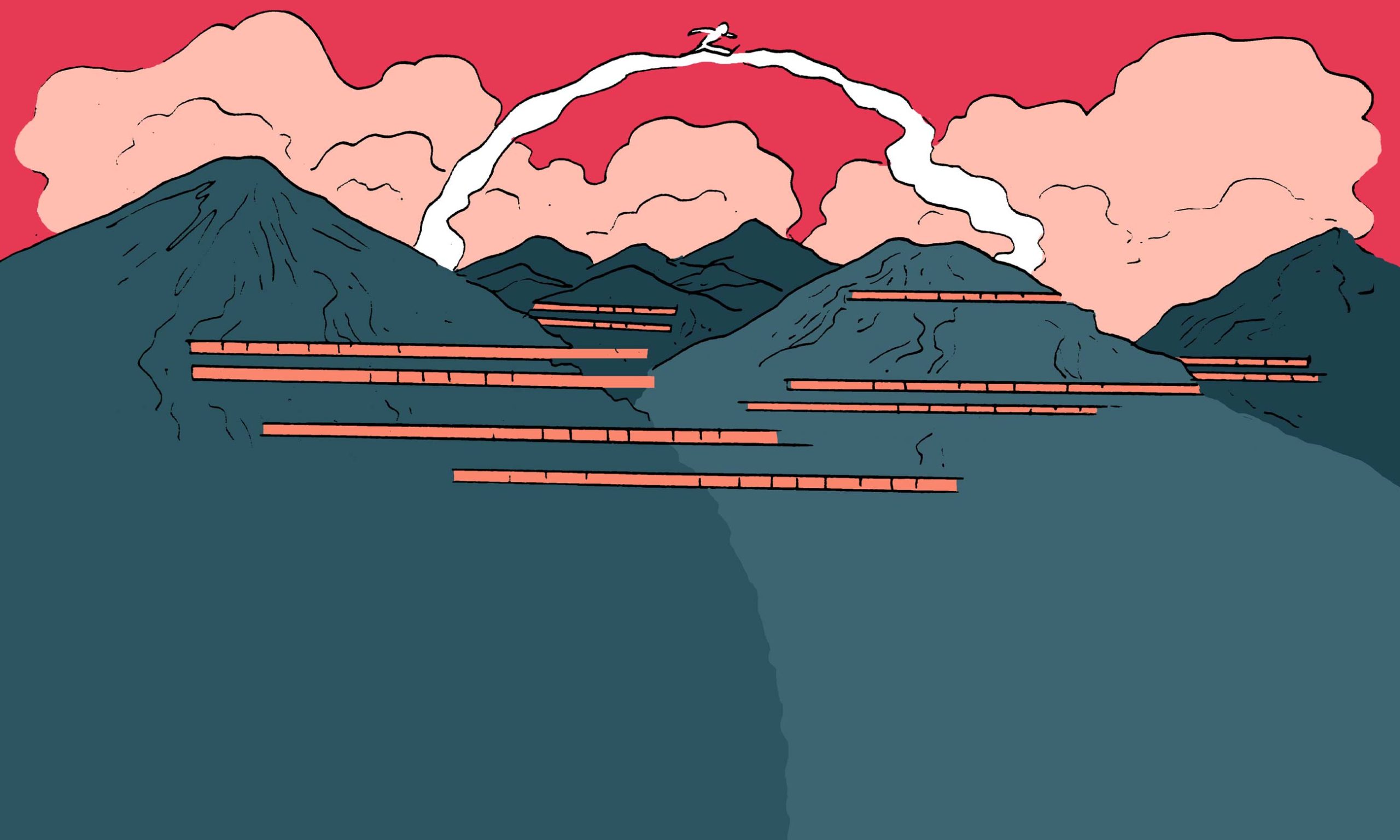

Twice a year at the charity event Games Done Quick (helpfully preceded by ‘Awesome’ in winter and ‘Summer’ in summer to mark the seasons), hundreds of thousands of people now gather around computer screens and in conference halls to watch speedrunners blitz through beloved games under an hour, half an hour, twenty minutes. They play ’em quick. Speedrunning, as its name might suggest, is the practice of playing a game to its authored conclusion as speedily as possible, and often by any means necessary. There are any number of categories for any number of games: ‘any%’ challenges the player to finish the game doing whatever they can, and it is the most popular category on the speedrunning scene today. At GDQ, there were live any% speedruns, multiplayer races, and blindfolded runs. The event has helped to skyrocket speedruns into well documented internet ubiquity. This year, GDQ raised over $2,000,000 for Doctors Without Borders, and it’s where the 2016 release of iD’s Doom (the great-great-great-grandchild of the 1993 release of the same name) was completed in just under an hour. The runner, who goes by the handle ‘blood thunder,’ jokes to the audience as he plays. He is personable, and more importantly, he is fast. He inches along invisible walls, leaps from railings to jump impossible heights, and uses explosive enemy deaths to launch him through closed doorways. As the game tries to give him a slice of plot early on in his 51 minute playtime, he laughs: ‘So, now we’re getting some of the story, which, if you’ve played Doom, you know no one cares about. And speedrunners? We really don’t care about it.’ To a speedrunner, it’s all map textures, skips, glitches, cyan doors and turkey dinners.

A good speedrun is hypnotising to watch – this goes for ones showcased at GDQ, or the ones which get circulated around the internet for their insane jumps or cutscene skips or lightning fast movement. They’re a dizzying show of hard won skill and palpable effort. The video of a world record time which knocks an hours-long campaign into minutes can be jaw-dropping. To consider the rise of this practice, it is impossible not to recognise the role and influence of iD Software’s Doom: speedrunning and early online collaborative documentation of gameplay are inextricably linked to the franchise. I talked to John Romero, and scoured the Usenet forum alt.games.doom (filter: from: 1993 to: 1996). I spoke to my friend Jazz Mickle (an all around Doom historian, mapper, musician and tinkerer) and to the speedrunner Zero Master (a world record holder, and credited with breaking an almost two-decade-long held speedrunning record) among others. Each person and every source made it clear that the speedrun culture we see today owes a lot to Doom, and is made up of a combined effort of countless people and hours. Any subculture is. To try and pinpoint any one piece of evidence for precedent over another is pointless; like trying to argue exactly when a snowball rolling down a hill picked up speed. But a trend can be profiled, or a cross-section offered. An evolutionary history can be proposed. This is what I have tried to do here – to present one way, one route, of how we can get to the finish line.

Lightning speed.[Doom is] really fast, and it’s a game that rewards your skill. Your skillful play. And speedrunning is the ultimate in skillful play.

Doom is a popular option for many speedrunners, but oddly enough, so is The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. They’re vastly different games, but share a significant five-year period in the early ’90s. Over the past decade, Ocarina has grown a huge following in the speedrunning community for its overwhelming catalogue of glitches and skips. Ocarina is a game I’m closer to than Doom and it presents an interesting parallel to the way that speedrunners approached the Doom franchise. Where Doom is largely glitchless, Ocarina’s speedrunners have, if you’ll indulge me, hacked the mainframe. Further, where Doom speedruns were able to be recorded from within the game, allowing for speedrunners to start sharing their accomplishments via e-mail shortly after its release, Ocarina fans had no such luck. The earliest video record of a speedrun I could find and watch is from 2006, using an internet archive. This run is over five hours long. The current world record, held by a user called Torje and using glitches, rests just over 17 minutes. Where the games overlap more significantly is in how these players talk about the practice of speedrunning. As Zero Master put it, any run relies on previous success. For them, the mantra is simple: ‘Try to copy the previous run, but do it a second faster.’ Narcissa Wright, a longstanding Ocarina speedrunner, was always quick to source her success to ‘group effort and a lot of man hours.’ In short, it takes a village to speedrun a game.

Speedrunning existed long before Doom. Really, it should be no surprise – people love to go fast. Cars, races, marathons, ultra marathons, triathlons, waiting in a queue – if it could go faster, it’s been attempted. As Romero notes, Doom is a fast game at its base, or as he puts it, ‘Lightning speed. It’s really fast, and it’s a game that rewards your skill. Your skillful play. And speedrunning is the ultimate in skillful play.’ But a lot of iD’s early games were fast. It was that Doom offered the ability to reliably capture footage from within the game which set it apart. Soon after this discovery, came the challenges, like those featured as Doom Honorific Titles1 – a collection begun initially by Christina ‘Strunoph’ Norman in 1994.

There were other challenges, which some users referred to as ‘Alternative Doom Games,’ including the very popular Tyson Mode, which requires that players never use any weapon but the fist, chainsaw, and the pistol. Sharing recordings of play online is what made these community-designed games not only possible, but thrive. Called demos, early recorded videos of Doom were easy to upload and disseminate. After all, demos were a KB or two – and Doom itself, only 4MB. This capability was offered in earlier games, Mickle told me, but simply didn’t work each time. ‘There were just some issues with Wolfenstein … a demo wouldn’t always work. But in Doom they fixed that.’

Doom offered a lot of sly fixes for fans to help them crack open the game. When I asked Romero if he knew what was happening on the internet with Doom, he stressed that it was seeing the fan-built levels in Wolfenstein 3D which really blew him away. ‘It was very, very difficult to make a level for Wolfenstein,’ he said. ‘It wasn’t made for anyone to make levels for it. But people figured out how to crack the coding so they could make their own levels … So when we saw people doing that – because we knew how hard it was for them to even get to that point – we obviously said, ‘Our next game has to be open.’ So, Wolfenstein really started it, but it exploded with Doom because we opened it.’

Suddenly, with just a command line parameter, anyone could record a demo of their play. This, coupled with the popularity of Usenet in 1993, brought on an onslaught of players sharing their accomplishments.

Doom was the biggest thing for people on the internet to be talking about. We’re talking about people making maps … people hacking the game to pieces and modifying the executable to change the game to make their own mods. Sharing it was big.

Usenet, according to the fan created Doom Wiki, was the ‘online birthplace of the Doom community in 1993.’ Doom’s popularity in other groups on the site necessitated its own subgroups, among which was alt.games.doom. This was also, incidentally, at the height of Usenet: the September before Doom’s release, the internet provider America Online moved away from exclusively offering access to Usenet to university students, and they began providing the forums to a larger section of its users. As more users found their way to the forums, so did more Doom players. Anyone who was anyone playing Doom, until the creation of a dedicated forum site in 1998 called Doomworld, was on Usenet.

‘Doom was the biggest thing for people on the internet to be talking about,’ said Mickle. ‘We’re talking about people making maps, people making new graphics, and sounds, people hacking the game to pieces and modifying the executable to change the game to make their own mods. Sharing it was big. There were just so many – so many – people doing it.’

Usenet offered the chance for people who loved Doom to find like-minded people – they shared anything from tips and tricks to experiences dreaming about the game, each post tinged with a sense of communal familiarity. ‘Man, I had the weirdest dream,’ wrote one user. ‘The layout in this dream had a similar floor plan to the first high school I went to, Vancouver Technical … for those of you familiar with its floor plan, you’ll understand how suitable it is for a level in Doom.’

Players talked about what wives and girlfriends thought of their new favourite pastime. This is not to say that women weren’t playing Doom – they were. According to a self-report Doom Usenet survey from 1994, 4% of the early online contributing users were women, and many other male users report seeing their girlfriends or neighbours playing the game. Women who self-reported, or pointed out that they were playing the game, however, were often met with hostility or further analysis from their male counterparts, as if trying to explain away their presence. ‘My GF doesn’t actually enjoy the game side of Doom. She enjoys the killing in it,’ says one user, before another remarks: ‘It would probably be scary seeing a female player with PMS playing Doom! hehehe :)’

That small number of women contributing to the Doom Usenet included Chris Norman, who ‘went by Chris at the time … to see if people would treat her differently on the net.’ In 1994, it was Norman who began the ‘first organised attempt’ of collecting the most impressive demos on what she called the LMP Hall of Fame. With a curated leaderboard to encourage them, players quickly began contributing their demos for Norman’s consideration, and an entirely online fan-built community of organised competitive play was born.

After Norman’s LMP Hall of Fame took off, a few other curated sites dedicated to competitive play followed suit. The most important of those were The Doom Honorific Titles, and a project hosted by Simon Widlake2 which would later become Compet-n: a database devoted to speedruns.

Here is a thing to know about Doom in particular: the end of level screen displays a number of statistics, one of which is simply called ‘Par Time,’ with no explanation. One player took to Usenet to ask others what it meant. ‘Does this par value represent how fast you can finish the level without grabbing anything? Has anybody made or bitten the par time?… I like to kill everybody and get everything before I move to the next level.’

The time shown in the games is actually John Romero’s time, rounded up to the nearest 30 seconds.

‘Wolfenstein, Quake, you know, all those games. I set all the times on those,’ Romero recalls. ‘With Wolfenstein, if you bought the Wolfenstein hint book, it says that I can finish the entire first episode in – I think – five minutes.’

I balked.

‘Can you?’

He laughed.

‘Uh, yeah. That’s why it was printed in the hint book. And so that was like, people who saw that were like, “That’s a challenge.”’

This is a theme which comes up again and again from speedrunners. ‘It’s a challenge,’ they say. ‘How fast can I get it?’ It’s a natural question to ask. When it comes to speedrunning games, there is no rulebook, no guide. There’s simply one possible way to do it, or one route which might be better than another. The game ceases to be the game it was authored to be, and becomes the landscape and language for an entirely separate practice. Players take what is given, and build something else out of it. It’s a kind of subversion, a subtle power play of guerrilla game design.

This is where that crucial characteristic comes into play to cement Doom’s place as a catalyst for speedrunning culture: it is, for the most part, glitchless. There are no level skips to get you to the end of the game faster, hardly any clipping through doors or falling through floors to reach an out of bounds area. This means that almost anyone can attempt a speedrun without much extra knowledge of the game, as its restrictions are more readily apparent. All it should take, in theory, is practise.

‘There’s a very solid game, there,’ said Mickle. ‘There’s only one actual glitch in the game that is severe.’

She paused, and I leaned forward expectantly.

‘Mostly, if you run diagonally,’ she said, ‘you run quicker.’

There exist purists who insist that a speedrun should be all about movement – that exploiting a glitch sullies a run. As it stands, Doom is all about movement. It’s possible that no one knows this better than the speedrunner Zero Master, who holds the current world record for Doom and Doom II, as well as a handful of others. Before them, the record belonged solidly to another player who went by the handle, ‘Looper.’ Looper also held the record for the fan-created levels, The Plutonia Experiment (which would later go on to be included in iD’s Final Doom), as well as a number of other difficulty/map combinations for the game. Looper held the longest of these records for 19 years. The second longest, for 11.

As Mickle explains it, Looper ‘was just the best speedrunner around. His movement was always perfect. He knew everything about Doom … He got a couple of tricks, which were very, very difficult to pull off. And they were 20 maps into the game. And the idea being that even if you managed to get up to there, you won’t have been as fast as him, because he just has perfect movement. And then you’ve got like, a 10% chance of pulling off this trick.’

There is a trick called a glide, where the player goes through a gap that is 32 units wide. This is extremely precise. It is not simply this movement, but hundreds of them. Minute turn upon minute turn.

Every year that passed after Looper set his record, no one really felt that they could attempt to beat his time. ‘People were like, ‘Oh is anybody challenging for the Doom II speedrunning leaderboard?’ As soon as, if you ever bring it up, everyone is like, ‘No, you can’t beat that.’ It just became like that. Then this one guy, Zero Master, never speedrunned Doom before … beat the record. Just came out of nowhere, sloppy movement, everyone just looked at this record and were like, holy crap.’

Zero Master is frank and thorough when they talk about speedrunning, and they are quick to credit the discovery of certain tricks to other runners, like King Dime. It’s not hard to see, however, that Zero Master is one of the most knowledgeable runners around. ‘Sometimes it is not obvious how things work because it requires some precise inputs,’ they say. ‘There is a trick called a glide, where the player goes through a gap that is 32 units wide.’ In brackets, they add, almost as an aside: ‘Doomguy [the player character] is also 32 units wide.’ In this manoeuvre, Zero must use a forward movement on the mouse rather than with the keyboard. ‘This is extremely precise,’ they stress. It is not simply this movement, but hundreds of them. Minute turn upon minute turn.

‘Eventually, I learned all the tricks,’ said Zero. ‘The next problem was getting through the maps alive.’

Damage is largely related to random number generation, abbreviated to a quick ‘RNG,’ and it is the bane of many speedrunners’ existence. Doom is no different. ‘Doom has a table of some 256 integer values between zero and 255 that the game uses to determine factors such as damage. Every time damage is dealt, it uses one of these values to determine the damage,’ Zero said. For a runner, however, it’s less about avoiding being hit by monsters, and more about avoiding hitting them. ‘A lot of Doom speedrunning is finding ways to get around monsters without colliding with them,’ they said.

Zero describes their process as reliant on three things: routing, practice, and actual attempts. They watch every run, even the slower times, hoping to catch a glimpse of a trick another runner may have figured out that they haven’t. Each step is crucially important, and it has taken them years to reach the level where they are now, using the routes they know best.

Routing for a runner is a practice in optimisation theory. Trying to figure out the best way to get from point A to point Z, and hitting all the other letters in between (if not in the right order). ‘Even after hundreds of hours, it could turn out that the route I was using was not particularly good,’ Zero said. This is the side effect of all good experimentation, and why you’ve got to run a game you love.’

After all the time Zero has spent mastering Doom, they feel there’s little room to improve. ‘There might still be a few things I could be better at, but reaching this point took two-and-a-half years.’ Two-and-a-half years for demo analysis, watching other runs, planning perfect runs and attempting to replicate them, perfecting mouse movement, and pouring over frame-by-frame recaps.

Perhaps there is, and all apologies to Greek philosophy, a kind of ‘Zero’s Paradox’ here. A run so well optimised, that the only way to improve is in milliseconds.

Or, perhaps, there’s something within the game where nobody has yet thought to look, as was the case with Ocarina of Time.

Now, when I was a kid, the Nintendo 64 belonged hard and fast to my older brother.

‘You can watch me play,’ he would say to me from the foot of the stairs in the basement. ‘But you can’t talk. And you have to sit behind the sofa so I can’t see you.’

Thicker than water, indeed.

Still, this was not a deterrent, it was a challenge. I sat, silent and stoic, from behind the sofa to get a peek of the console in action. We owned the four requisite N64 games: GoldenEye 007, Mario Kart 64, Super Mario 64 and the jewel of jewels, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. When my brother wasn’t home, or somewhere else in the house, I’d creep into the basement and revel in the illicit luxury of sitting on the sofa. I’d blow air into the cartridges and slam them into the machine with a satisfying and cathartic thwack. Later we would get Mario Tennis and Majora’s Mask. I liked Princess Daisy’s hair, and I both had a crush on Link and thought he was a girl. I knew every inch of the Kokiri Forest, and I could beat my brother’s time for Epona’s horse race. When I drew Triforces on my jeans with a Sharpie, my mother went ballistic. To me, Ocarina was everything I wanted out of a videogame, and I know I am not alone in this. Zelda games are omnipresent in most gamers’ histories, and Ocarina consistently tops charts like ‘Top 10 Videogames You Must Have Played By Now!’ or, ‘BEST VIDEOGAMES OF ALL TIME,’ or, ‘You Want The Games That Are The Best, Now Here They Are In One Handy List For You, And By List We Mean Disappointing Slide Show.’ Ocarina is a game which has almost been played to its cultural plateau – we know all the lines, the jokes, the secrets, the iconography. It is, perhaps even with our nostalgia goggles on, beginning to show its age.

This mix of age and a vice grip of nostalgia is perhaps what has made the game perfect for the speedrunning scene today – it wasn’t until around 2006 that the game began to be broken into in earnest. Originally, Ocarina speedrunners like Mauri Mustonen, who went by the online handle ‘Kazooie,’3 managed to get a mostly glitchless4 runtime of the game to just under five hours. This record beat out previous runs from a player, whose times were not properly recorded or archived. This is crucial, and recalls an important lesson from Doom running: the archive is king. The most important thing for early Ocarina speedrunners were Kazooie’s 2006 videos.

2006 is also the year after the video sharing website YouTube was launched, and the same year that Narcissa Wright, a longtime speedrun record holder for Ocarina, began using the Speed Demos Archive forums to talk about the game. With both a community and the capability for easy video sharing in hand, folk experimentation could begin. Narcissa credits the inspiration for early experimentation in the game to Kazooie’s videos, and specifically, certain jumps. Narcissa describes this period of time from 2006 to 2008 as one of rich experimentation. Few speedruns were actually attempted in this two year period, opting instead for creating a catalog of glitches from hours of chipping away at the game environment, or planning possible routes with what they knew already. ‘In fact,’ she said in a video commentary,5 ‘it felt more like we were doing science than anything else.’

Those original Speed Demos Archive threads were a hotbed. There are upwards of 6,000 posts on any one thread, and there are hundreds of them dating back to 2005. Runners used these forums, under thread titles like, ‘Oot Secrets and Strategy Conference’ to ‘Sub 4 (It may happen)’ to strategise, theorise, and dream of a run under four hours. Narcissa told CVG magazine in 2013 that whenever anyone found anything new, ‘their first inclination is to share it and let people know. For the people who find that stuff, the reward is just finding it, not necessarily using it to beat the record.’

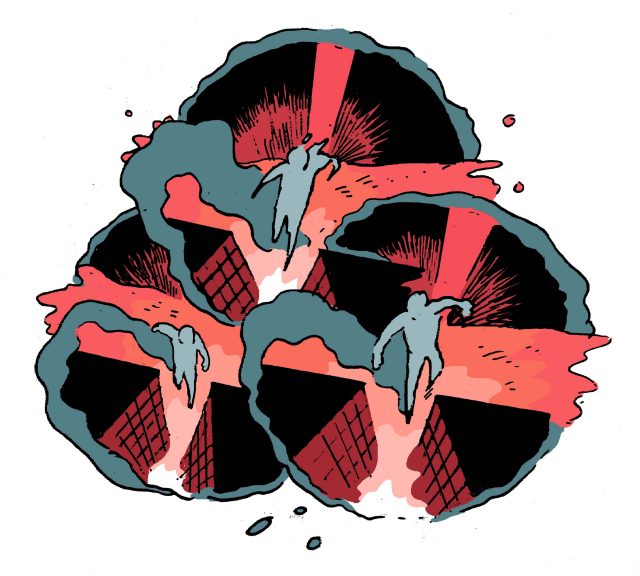

Over time, these glitches began to add up, stitching pieces of different glitches together, slowly shaving off minutes. By mid-2008, runners had collectively figured out how to manipulate items in Link’s inventory to trigger a late game cutscene, and use a ‘tricky side-hop jump-slash’ to jump into the Temple of Time before they were meant. This was a huge victory for the community, as it shaved off up to 10 hours of gameplay. Skipping into the Temple meant grabbing the Master Sword without completing any dungeons as Young Link, and players could combine this with item manipulation to complete the game without any temples at all. After three years of experimentation, runners could get a tool-assisted run down to 2:40:58. All they had to do was replicate it.

In the two and a half years that followed, minutes were dropping from world records left and right. In September of 2011, the hour mark was broken when a user called ‘maxx’ uploaded a 0:59:55 run, and not even two months later, someone knocked it down to 0:57:25. Times were falling faster than anyone could keep up with, and world records bounced back and forth.6 But at this point, they’d hit a wall. The community felt that the perfect run had been found, and they’d hit the same Zero’s Paradox described above. Any advancements in a record time would rest solely on finesse and incrementally faster movement, rather than on any significant route improvements or new glitches.

A few months later, just when the community was beginning to settle, the floodgates opened again.

A user called ‘ChristianF23’ found a way to skip several post dungeon cutscenes using a glitchy warp sequence, and – as Narcissa put it – ‘the Zelda scientists went to work.’ They experimented new routes and combinations, finding warps to anywhere from the Forest Temple, a beta cutscene in Jabu’s belly eventually cut from the game, and even the end credits. The game fell apart in front of them, and they were desperately trying to put the most efficient pieces end to end. ‘That night we all got on Skype and spent hours and hours trying to mess with that glitch, it was so weird,’ she recalled.

Two users going by ‘Sockfolder’ and ‘robdog’7 were eventually able to come up with and test a theoretical list of these warps, and they found one which blew the entire community away: if done correctly, one could warp Link from the first dungeon’s final boss to the last sequence of the last battle of the game. Theoretically, the game could now be beaten in 22 minutes.

Since this discovery, the world record for Ocarina has dropped incrementally. Twenty-two minutes in 2013 to Narcissa’s storied 0:18:10 in 2014. These days, the title gets handed back and forth every few weeks or so between two runners: skater82297 and Torje. On Christmas Day 2016, Torje dropped the records to 0:17:13. Skater matched the record at the beginning of March 2017, only for Torje to crack 17:09 not even two weeks later.

Perhaps the time could continue to drop this way, or maybe this is just another Zero’s Paradox. It could be that there is nowhere left to go with Ocarina of Time. At least Torje remains hopeful. The video description for his Christmas Day record signs off simply:

‘Will go faster soon.’

He did.

Footnotes

- 1 Around this time, in a forum post simply and ominously titled, ‘challenge’ on the newsgroup, one player demanded: ‘PLEASE don’t even think about challenging me if you can’t finish all 3 levels of doom with all secret rooms found and all monsters killed, on ultraviolence without dying once OR saving the game. Don’t even read this message if you use the cheat modes.’ I’ve never used a Doom cheat mode, so I suppose I am exempt.

- 2 Simon Widlake passed away in 2003. Perhaps fittingly, his page on the Doom Wiki also serves as a small memorial. ‘He took part in many forums, but few people could work out what the hell he was talking about half the time,’ wrote a contributor. Beneath it, Widlake’s brother responds: ‘It’s OK, his family could not work out what the hell he was going on about half the time either.’

- 3 Yes, the Zelda speedrunner’s name is Kazooie. This is very confusing, and made Google searches difficult.

- 4 In actuality, the run is without ‘non-severe’ glitches. None of the glitches Kazooie uses are able to skip any portions of the game which the community deems ‘significant.’ It is the earliest verifiable documentation I can readily find of these early speedrun attempts for Ocarina.

- 5 It should be mentioned that Narcissa took this video down shortly after posting it, likely due to internet harassment regarding her being a trans woman, and the use of an incorrect, dead, name. I refer to the video here to highlight the unique significance of her in-depth commentary, discussion of her process in developing this run, and her hugely formative contribution to the contemporary speedrunning landscape.

- 6 A dedicated and consistent leaderboard, tracking these times wasn’t in place until 2013 or so. I’m going by YouTube upload dates here, which occasionally can be misleading, due to reuploads. To find each video’s original post in the SDA forums would be preferable, but I simply do not have the time. Anyway, this upload has quite possibly my favourite upload text of any speedrun I have seen. ‘From reset to final kill. There are some mistakes.’ A classic.

- 7 Rarely does one get to hear the phrase, ‘Sockfolder tested robdog’s theory,’ said so earnestly, and for this I thank Narcissa Wright.